American Academy of Pediatrics Feeding Guidelines One Year Old

Am Fam Physician. 2018;98(4):227-233

Patient information: See related handout on toddler nutrition.

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

The establishment of eating practices that contribute to lifelong nutritional habits and overall health begins in toddlerhood. During this time, children acquire the motor skills needed to feed themselves and develop preferences that affect their food selections. Classifications for faltering weight (also called failure to thrive or growth faltering) and overweight are based on World Health Organization child growth standards (for children younger than two years) and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention growth charts (for children two years and older). Breast milk or whole cow's milk should be offered as the primary beverage between one and two years of age. Sugar-sweetened beverages should be avoided in all toddlers, and water or milk should be offered instead. Allergenic foods such as peanuts should be introduced early to infants at higher risk of allergies. Vitamin D and iron supplementation may be advisable in certain circumstances, but multivitamins and other micronutrient supplements are usually unnecessary in healthy children who have a balanced diet and normal growth. Optimal food choices for toddlers are fresh foods and minimally processed foods with little or no added sugar, salt, or fat (e.g., fruits, vegetables, lean protein, seeds, whole grains). Parents and caregivers are responsible for modeling healthy food choices and dietary practices, which shape children's food preferences and eating behaviors. Parents should avoid practices that lead to overeating in toddlers (e.g., feeding to soothe or to get children to sleep, providing excessive portions, pushing children to "clean their plates," punishing with food, force-feeding, allowing frequent snacks or grazing). In general, parents should use the approach of "the parent provides, the child decides," in which the parent provides healthy food options, and the child chooses which foods to eat and how much.

During the transition from a liquid-based infant diet to a diet more typical of older family members, toddlers have their first exposures to many food types and are experiencing rapid growth. This period marks the establishment of eating practices that contribute to lifelong nutritional habits and overall health. At this age, children learn the motor skills needed to feed themselves and develop preferences that affect their food selections.

WHAT IS NEW ON THIS TOPIC

Although the American Academy of Pediatrics supports the consideration of reduced-fat milk instead of whole milk in toddlers who are at risk of obesity or cardiovascular disease, early introduction of reduced-fat milk may ultimately increase the risk of obesity and should be avoided in most cases.

In a sharp departure from previous recommendations, more recent guidelines recommend early introduction of potentially allergenic foods (e.g., peanuts) into the diets of some infants. Therefore, foods that were traditionally started in toddlerhood may now be given earlier.

Monitoring growth is a primary method of assessing over-and undernutrition. The World Health Organization child growth standards should be used for children younger than two years, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention growth charts should be used for children two years and older.1 Both are available for free at http://www.cdc.gov/growthcharts.

Standards for classification of overweight and obesity are relative to age and sex. In children older than two years, body mass index in the 85th to 95th percentile is considered overweight, and a body mass index in the 95th percentile or greater is considered obese.

Although there is no clear consensus on its definition, faltering weight (also called failure to thrive or growth faltering) may be defined as measuring less than the 2nd or 5th percentile and a pattern of growth over time that declines across two major percentile lines on standard growth charts. This topic was reviewed previously in American Family Physician.2

General Principles

The typical American diet that many young children are exposed to is dominated by calorie-dense, processed foods high in fat, sodium, and simple sugars. The 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans recommends that adults limit consumption of added sugars to less than 10% of calories per day, and instead encourages lean proteins, reduced-fat dairy products, whole grains, fruits, vegetables, and seeds, with little or no added sugar, salt, or fat.3 Whole foods from plants are good sources of complex carbohydrates, fiber, vitamins, and minerals and allow children to feel full longer. Consumption of these foods during childhood has been correlated with a reduced risk of overweight and obesity later in life.4 Table 1 provides examples of well-balanced meal plans appropriate for moderately active children.3,5,6

Special diets for health promotion have become popular; however, they are not recommended in toddlers unless indicated for specific medical conditions. For example, a gluten-free diet can be deficient in vitamins, iron, and dietary fiber because gluten-free grains are often not enriched. There is no evidence that a gluten-free diet has any benefit for those without celiac disease.7 Additionally, special diets may be expensive and challenging to follow, making it difficult to achieve adequate intake of nutrients.

Food and Nutrient Recommendations

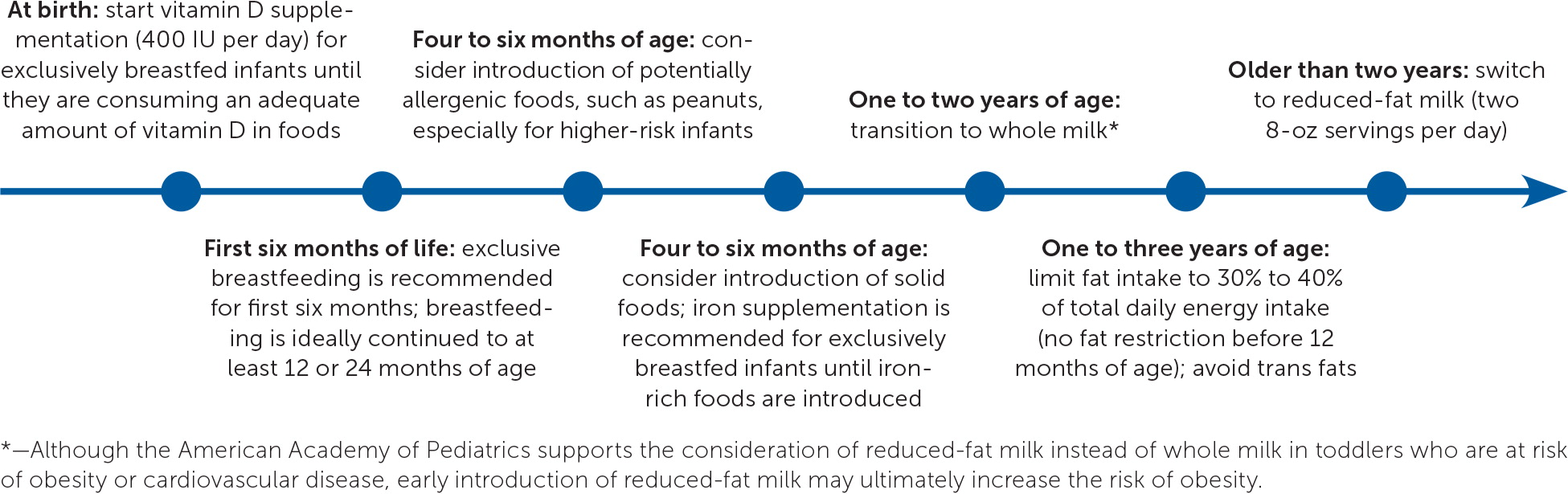

Figure 1 is a timeline for introducing key foods when transitioning from the liquid-based infant diet.8–13

BREAST MILK/FORMULA

Exclusive breastfeeding is recommended for the first six months of life, and breastfeeding should be continued up to at least 12 months of age per the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and American Academy of Family Physicians, or up to at least 24 months of age per the World Health Organization.9–12 The addition of solid foods can be considered between four and six months of age, as developmentally appropriate. The addition of formula, rather than milk or other beverages, is recommended if breastfeeding is decreased or discontinued before 12 months of age.12

MILK

Cow's milk provides key nutrients, such as protein, calcium, and vitamins A and D. Observational studies support a recommendation of two 8-oz servings of cow's milk per day in toddlers to maintain adequate vitamin D and iron stores.14,15 Children one to two years of age should drink whole milk rather than reduced-fat milk.8,16,17 Although the AAP supports considering reduced-fat milk for toddlers who are at risk of obesity or cardiovascular disease,17 early introduction of reduced-fat milk may ultimately increase the risk of obesity.18–20

If an alternative to cow's milk is preferred, fortified soy milk is most similar in composition to cow's milk.3 Other alternatives, including almond, rice, coconut, and hemp milks, tend to have less protein and fat compared with cow's milk, and have been associated with decreased adult height and lower vitamin D levels.21,22

OTHER BEVERAGES

Daily intake of 100% fruit juice should be limited to 4 oz between one and three years of age and 4 to 6 oz between four and six years of age.23 Juice should be offered only in an open cup, not a bottle or sippy cup. Sugar-sweetened beverages (e.g., fruit drinks, sweetened bottled water, sports drinks, soda) are associated with obesity and dental caries, and should be avoided entirely.24 Water is the best option for toddlers between meals for hydration with no additional calories.

MACRONUTRIENTS

Fat intake should not be limited before 12 months of age because of its importance in neurologic development. Between one and three years of age, fat can be safely limited to 30% to 40% of total daily energy intake. Polyunsaturated fatty acids and monounsaturated fatty acids are the preferred sources of fat. There is conflicting literature about restrictions on saturated fat and dietary cholesterol.3,16,25 Trans fats should be avoided entirely.3,16 Different dietary fat sources are listed in Table 2.3

Protein should comprise 5% to 20% of daily energy intake from one to three years of age.3,26 Limited evidence shows an association between a low-fat, high-protein diet and overweight and obesity later in life, suggesting the importance of balanced macronutrient composition in toddlerhood.27–29

Carbohydrates should comprise the largest percentage of macronutrients, at 45% to 65% of daily energy intake, in children one to three years of age.3,26 Complex carbohydrates such as vegetables, whole grains, beans, and lentils are preferred over simple or refined, processed carbohydrates. Added sugars should be avoided in children younger than two years and limited in older children.24

Foods rich in dietary fiber tend to be nutrient-dense and contain fewer calories. Dietary fiber from unprocessed or minimally processed foods is recommended because it has been associated with lower body fat composition and better cardiometabolic health later in childhood.16,30 The recommended amount of fiber intake for toddlers is 14 g per 1,000 kcal, or at least age plus 5 g per day.3,16

MICRONUTRIENTS

Vitamin D and calcium are essential for bone growth and bone mass acquisition. The recommended daily intake of vitamin D for children one to three years of age is 600 IU.3,31 The AAP recommends vitamin D supplementation (400 IU daily) for exclusively breastfed infants until they are consuming an adequate amount of vitamin D in foods, with consideration for more if there is risk of vitamin D deficiency (e.g., in those with chronic malabsorption).31,32 The recommended daily intake of calcium for children one to three years of age is 700 mg.3,31 There is 276 mg of calcium per 8 oz of whole milk. Nondairy sources of calcium include green leafy vegetables, legumes, nuts, and fortified cereals.31

Iron deficiency and iron deficiency anemia in young children have potential neurodevelopmental implications. Infants between six and 12 months of age should consume 11 mg per day of iron, and children one to three years of age should consume 7 mg per day.33 Risk factors for iron deficiency anemia include low socioeconomic status, lead exposure, prematurity, low birth weight, high intake of whole milk, and consuming low-iron foods.34

The AAP recommends iron supplementation (1 mg per kg per day) starting at four months of age for exclusively breastfed infants until iron-rich foods are introduced; universal screening for anemia with hemoglobin at 12 months of age is also recommended.33 The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force and American Academy of Family Physicians conclude that evidence is insufficient to recommend for or against routine screening for iron deficiency anemia in asymptomatic children six to 24 months of age.35–37 Prevention of iron deficiency in young children includes use of iron-fortified formula in formula-fed infants, consumption of iron-rich foods at the appropriate age, not introducing cow's milk before 12 months of age, and limiting cow's milk to 16 oz per day once it is introduced.34,38 Although certain high-risk groups have shown improvement in long-term outcomes from iron supplementation, it is not routinely recommended in low-risk infants and toddlers.35

Multivitamin supplementation is usually unnecessary in healthy toddlers and children who eat a balanced diet and have normal growth, and it may increase the intake of nutrients to above the recommended maximal levels. Nutrition through the intake of foods is preferred, unless the child is at particular nutritional risk (e.g., those with chronic disease or faltering weight).3,39 Table 3 includes examples of nutrient-dense foods for toddlers.3

Food Allergies

In a sharp departure from previous recommendations, more recent guidelines recommend early introduction of potentially allergenic foods into the diets of some infants. Therefore, foods that were traditionally started in toddlers may now be given earlier. For example, foods containing peanuts should be introduced between four and six months of age in infants with severe eczema or egg allergy (after serologic or skin prick testing) and at around six months for those with mild to moderate eczema. In children with no eczema or food allergies, peanuts can be introduced as usual with other age-appropriate foods.13 The new peanut recommendations were previously summarized in American Family Physician.40

There is limited evidence that allergen exposure through breastfeeding reduces future allergies.41 However, there is insufficient evidence to make recommendations for maternal food preference or avoidance while breastfeeding or for the use of infant supplements such as probiotics to affect the risk of food allergies.42

Common Challenges and Behavioral Recommendations

Parents and caregivers serve as the primary models for healthy eating and activity patterns, and are responsible for food selection and portion sizes, determining the timing and social context of meals, and influencing other associated behaviors such as screen time, playtime, and sleep schedules.43 Some traditional feeding practices may negatively influence eating patterns, promote early obesity, and foster picky eating. For example, parents and caregivers should avoid feeding to soothe or to get their children to sleep, providing excessive portions, pushing children to "clean their plates," punishing with food, force-feeding, or allowing frequent snacks or grazing.43,44

PICKY EATERS

Between 25% and 50% of normally developing children are picky eaters.45 Although toddlers' appetites and how much they eat may fluctuate considerably from day to day (by up to 30%), they are able to self-regulate without significant detrimental effect on growth. Children may reject unfamiliar foods initially but accept them once they become more familiar. Providing frequent opportunities to try new foods, sometimes 20 to 30 offerings, is recommended to increase familiarity.46 However, forcing or pressuring children to eat new foods such as vegetables can promote dislike of those foods, particularly if more appetizing foods are available.47 Flavor conditioning is recommended when introducing unfamiliar foods. This involves pairing new flavors with familiar flavors to promote associative learning. Similarly, food chaining includes presenting new foods along with previously accepted foods that are similar in taste, texture, or temperature.48 Selection of foods is also influenced by the choices of peers and adult models; children are more likely to taste unfamiliar foods if they see peers and caregivers eating those foods.44

The clinician should distinguish picky eating from a pediatric feeding disorder, which is defined as a significant impairment of oral intake lasting more than two weeks that is not age-appropriate and results in substantial medical, nutritional, and emotional consequences. Pediatric feeding disorder is most common in young children and affects an estimated 3% to 10% of all children.49 If a pediatric feeding disorder is suspected, a multidisciplinary approach to the evaluation should be considered, including possible referral to a speech pathologist, registered dietitian, clinical social worker, behavioral psychologist, pediatric gastroenterologist, developmental pediatrician, or dedicated feeding team.49–51

OVEREATING

Self-feeding in toddlers should be encouraged to promote fine motor skills and regulation of food intake.46 The foods provided should be appropriate to the toddler's developmental ability and cut small enough to avoid choking. Children should be encouraged to use child-sized cups and utensils. Overeating is worsened when cheap, high-calorie, palatable foods (i.e., junk foods) are available, and offering large portions of these foods has been correlated with greater consumption compared with offering smaller portions.52

The AAP offers guidance on toddler feeding and emphasizes the approach of "the parent provides, the child decides."53 In most instances, when a parent provides healthy foods at meal and snack times, the child is able to appropriately choose how much and which foods to eat.53

Data Sources: PubMed, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and Essential Evidence Plus were searched using terms such as toddler nutrition, preschool nutrition, and childhood feeding. The search included randomized controlled trials, meta-analyses, clinical trials, and clinical reviews. Search dates: April and June 2017, and February 2018.

The authors assume full responsibility for the ideas and opinions expressed in this article, which should not be considered the opinions of the U.S. Air Force or the Department of Defense.

Source: https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2018/0815/p227.html

0 Response to "American Academy of Pediatrics Feeding Guidelines One Year Old"

Post a Comment